AUSTIN, Texas – After discovering the remains of 36 people beneath the floors of a chapel in Austin’s oldest public cemetery, the city is turning to DNA analysis in hopes of discovering their long lost descendants.

What You Need To Know

- Remains of 36 people were found beneath the chapel in 2016

- Oakwood is the oldest public cemetery in Austin

- City to test DNA in search for possible descendants

- Community will be able to submit their own DNA samples

That’s why Kim McKnight, the program manager for Historic Preservation and Heritage Tourism with the Austin Parks and Recreation Department (PARD), says she was shocked to receive the call that archeologists had discovered bone fragments beneath the floors of the Oakwood Cemetery Chapel in 2016.

The chapel was undergoing a complete restoration funded by Austin residents through the $4 million PARD Cemetery Master Plan bond passed in 2013, but construction was stopped immediately.

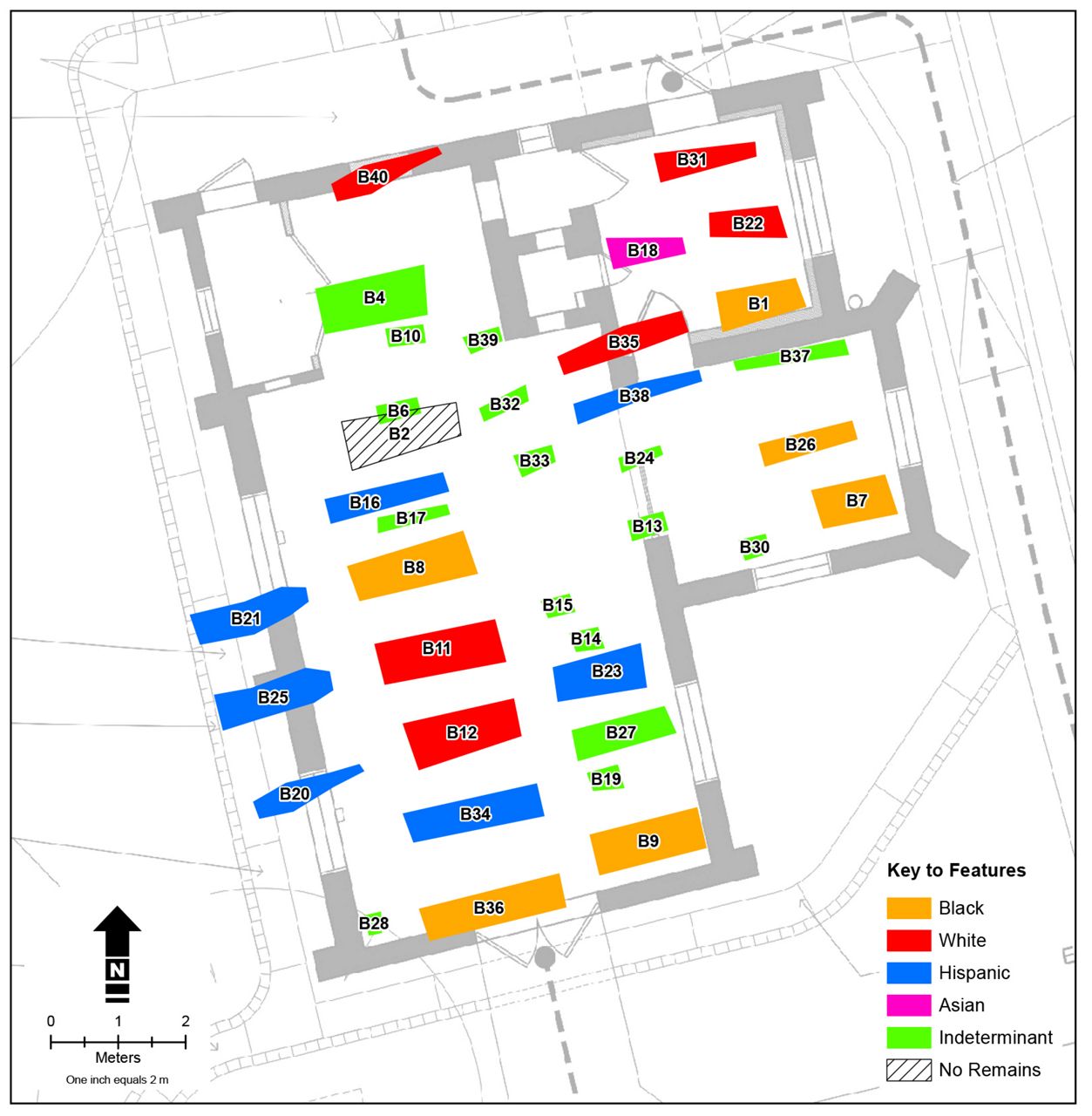

After months of community engagement and work by a team of archeologists, the remains of 36 people, including 16 children and infants, were uncovered.

No one expected to find the remains under the chapel floors, but there they were.

Who were these people? Why had they been forgotten? What is our responsibility to them today? These are the kinds of questions the city has been trying to answer in the four years since.

Oakwood Cemetery: A History

The Oakwood Cemetery, originally named “City Cemetery,” was established in 1839 as a 10-acre public cemetery on what is today, Austin’s east side.

That was the same year Waterloo, now known as Austin, became the capital of the Republic of Texas.

The cemetery’s borders grew with the population of the newly founded city. Those who could afford it purchased family plots, and when you walk its rows today, you’ll notice the names of famous Austin landmarks, such as Zilker and Pease.

Segregation didn’t come to Oakwood Cemetery until 1859 through an ordinance from the mayor that divided the cemetery in two. Wealthy white families were buried south of Main Avenue, while people of color – some believed to be slaves – were buried on the north side of the road in a section dubbed the “Colored Grounds” in historic documents.

Those grounds became the final resting place for not only people of African descent, but for anyone deemed other: the poor, individuals of Mexican descent, “strangers” from out of town.

In 1914, a women’s auxiliary group built a chapel on those same grounds. According to Jennifer Chenoweth, the museum site coordinator for Oakwood Cemetery Chapel, they were trying to, “raise the standards of how we mourn our dead in Austin.”

The chapel had enough room to host funeral services and house the dead prior to burial.

“We don’t know what they knew at the time [the chapel was built],” explains McKnight. “…we can’t assume and we certainly not going to make any excuses for the decisions that were made at that time.”

It wasn’t until the chapel had fallen into a state of disarray and the city started renovations that it was discovered the chapel had been built on top of graves.

“The first burial in the cemetery happened in 1839. And we don’t have written records of the burial ledgers – burial ledgers weren’t kept until 1859. So for 20 years, there were a few people we don’t know exactly where they were buried,” says Chenoweth.

But even burials that were documented leave us little information about who these people were.

“The way that the records were kept – it was incredibly disregarding,” says Chenoweth, “To not even put someone’s name in the record book and to list them by their ethnicity alone or recount the tale of their murder without a name – it is incredibly sad to me.”

Archeologists Provide Some Answers, But Also More Questions

As the archeology team from Hicks & Company started digging in 2016, they weren’t just looking for more remains. They were looking for details that could help paint a picture of who these individuals were.

While the ethnic origins of the children and infants could not be determined, researchers looked at the skull shapes of the adults to discover information about their ethnicity.

Brandon Young, an archeologist who helped prepare the Archeological Monitoring and Exhumations report for the City of Austin, says there was a concern that many of the bodies would be of African descent because of where they were located in the cemetery.

But of the 20 adults, Chenoweth says about a third were white people – likely impoverished or visiting from out of town – another third were of Mexican descent, and the final third were Black people, likely slaves or former slaves. One person of Asian descent was also found.

Researchers say this could mean that they were buried in the order they died instead of in designated sections.

Another puzzle piece archeologists hoped to find: personal belongings buried with the dead.

Most of the objects recovered though were hardware from coffins, like nails and screws, or buttons and keys.

Two objects that did stand out: a gold ring found on the middle finger of an adult man’s right hand, and a white porcelain crucifix placed on the chest of a small child.

Young says another point of interest came from what they didn’t find. There were no physical signs that pointed to how these people died.

Yes, there were fractures and broken bones, just nothing that pointed to their exact deaths.

One possible explanation Young points to: deaths caused by infectious diseases – a reality that hits hard in 2020 amid a global pandemic.

Chenoweth, McKnight, and Young each talk about how learning as much about these people as possible has a way of strengthening our connection to them.

“The struggles that they have are a lot of the same struggles we have today. We have economic choices that make us make decisions for our families we don’t want to have to make. We work hard, we sacrifice, we grieve, we love, we have hopes for our children, and that is the same as all of the people buried here,” says Chenoweth.

City Turns to DNA Analysis for More Answers

Since the remains were exhumed, they’ve been stored at the Texas State Forensic Anthropology Center.

There is still a section outside the church archeologists need to examine, but the city hopes they will eventually be able to reinter the remains at Oakwood if no additional graves near the chapel are found.

If there are, the 36 will be buried in another Austin cemetery that has more space.

But before that happens, the city is turning to science in hopes of learning more about these people.

Soon, the 20 adults will be shipped to the University of Connecticut where researchers will test their DNA. There isn’t enough genetic material from the children and infants to test – those remains will stay at Texas State University until they can be reinterred.

The likelihood of finding living descendants, Young admits, is small, but there is still a lot of information that can be learned from the analysis.

“There’s also a lot of other things that can be found about these individuals like, potentially the regions that they originated from or other aspects of their life that can be in their DNA,” explains McKnight.

Young adds there is also a chance of finding information in their DNA about how they died as well.

As part of the DNA collection, the city will ask residents to contribute their own samples to see if they can find any living descendants.

Online Symposium to Detail Findings, Look Towards Remembrance

This Friday and Saturday, the city is hosting a two-day online symposium about the cemetery chapel remains.

Participants on Friday will hear from Young’s team of archeologists about its findings, as well researchers from Texas State University. Leaders will also discuss what’s next regarding reinternment and how community members can donate a DNA sample for testing.

On Saturday, the focus will shift to how these people will be remembered going forward.

“In 2019, when we opened the chapel [following the renovations] we talked to our community groups, especially people of color or people who had a real stake in this cemetery. And every single small group of people we interviewed said, ‘Well, in my family…’ or ‘In my culture…’ Remembering someone or even naming descendants after one of their ancestors was all part of envoking that name and continuing [their] family heritage – in every group I talked to,” Chenoweth says. “So that kind of reinforced how important it is to name someone – to keep their memory, their spirit, their honor, and their tradition, and where we came from alive.”

Chenoweth and McKnight both say figuring out how to honor and remember these people has been a priority of the city since their discovery.

“We’re doing the opposite of sweeping it under the rug,” says McKnight. “We’re really pulling it into the light, and trying to be transparent with what we found and try to take ownership for what we think is of a pretty serious injustice from long ago and doing our best to learn from this.”

Even though these 36 people were lost to us more than 100 years ago, community members today will get to have a say in how they are remembered going forward, so they cannot be lost to time again.

“They were just trying to be. To try and exist and live and have a home in a place, in a community, which is the same home and place and community we all share here in Austin. So whether you were related to them or not, they are your forbearers. Culturally they helped create Austin,” Chenoweth says.